What does it mean to persist in a world that offers no true justice? In the parable of the persistent widow and Jacob’s wrestling with the angel, we see not just human striving, but a divine call to unyielding hope. This Sunday, dive into a message that unveils the emptiness of humanism’s “standardless standard” and points us to Christ, the true vindicator who fulfills God’s promise. Join us to explore how the elect are called to see God face to face—not through effort, but through faith in the Messiah who strove for us. Don’t miss this reflection on where true hope lies in an exhausted world.

Proper 24

Psalm 121; Genesis 32:22-31; 2 Timothy 3:14-4:5; Luke 18:1-8

You can also subscribe to this podcast on Apple, Spotify, or YouTube.

I.

The parable of the persistent widow and the unjust judge has a simple interpretation. Unlike many parables, Luke even tells us beforehand what that is: “And he told them a parable, to the effect that they ought always to pray and not lose heart.”

But is there more to it? Is it the call to persistence — particularly to persistence in prayer — that it seems? I don’t think so, and the reason I don’t think so is found in the judge’s reason for giving the widow what she wants. He says: “She will wear me out by her continual coming.”

Is the purpose of prayer to wear out God? Hardly, no more that it is possible to drain the ocean with a straw. Human will, human persistence, is nothing compared to the creative and destructive power of God. This is not a parable about getting what you want, spiritual or otherwise, by hard work and persistence.

I think it’s fair to ask if the parable is even about prayer. In so far as Luke says it is, we must acknowledge that it is: “He told them a parable to the effect that they ought always to pray and not lose heart.” But if it’s about prayer, it’s certainly not a tutorial.

This parable is not a how-to-pray, like we find in Luke 11, when the disciples say to Jesus, “Lord, teach us to pray, as John taught his disciples.” Instead, the focus is on the second part of verse one: “pray and not lose heart.” But what would cause us to lose heart? It is to that question we now turn.

II.

The parallel reading from the Old Testament, Genesis 32, makes the same point about not losing heart. In verse 26, Jacob says to the angel he has been wrestling, “I will not let you go, unless you bless me.” No one who has lost heart could say such a thing. I spoke at length last week about demoralization. Jacob emerges from his struggle with the angel thoroughly re-moralized.

The result of Jacob’s striving is that he becomes one of the few — those to whom Jesus refers to in today’s Gospel reading as “the elect” — who are chosen to see God face to face. “For I have seen God face to face,” Jacob says, “and yet my life is preserved.”

Both readings today are about the longing, the hope, of seeing the Messiah, the Christ. That is how the stories of Jacob’s wrestling match and the widow’s incessant petitioning are used in the text. It is striking to read of Jacob in a boxing match with God. It is surprising that the judge caves to a nagging widow. However, neither Jacob’s fight nor the widow’s persistence is the point.

The key point is that both stories show us what it’s like to live with messianic hope, to live like you are one of the elect, to live like you are chosen to see God’s face.

As Jacob’s story begins, we are reminded of his “two wives, his two maids, and his eleven children” and that he sent them along with “everything that he had” across the river Jabbok.

Genesis 31 tells that “everything that he had” was considerable, Jacob having grown rich while working for his father-in-law, Laban. Jacob is already a blessed man.

Earlier in Chapter 32, Jacob says to God, “I am not worthy of the least of all the steadfast love and all the faithfulness which thou hast shown to thy servant, for with only my staff I crossed this Jordan; and now I have become two companies.” This means that Jacob’s demand is for a spiritual blessing. He already acknowledges that he has more material abundance than he deserves.

The spiritual blessing Jacob craves is tied to God’s covenant promise to Jacob and his descendants. In Genesis 32:12, Jacob even reminds God of His covenant promise: “...thou didst say, ‘I will do you good, and make your descendants as the sand of the sea, which cannot be numbered for multitude.’”

This means more than Jacob can possibly know as he speaks these words. All hope is like that. All faith is like that. St. Paul says in Hebrews 11:1 that “...faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” If we have not yet seen these things, then surely the hope is that they are greater than we can possibly imagine.

The story of Jacob’s struggle with the angel is set in the tense time before his reunion with his brother Esau. In Jacob’s mind, his prayer is likely no more than a plea for God to spare his two wives and eleven children so that the covenant promise can be fulfilled. After all, if Esau kills his brother Jacob’s wives and children, then the covenant is a dead letter, the promise to make Jacob’s “descendants as the sand of the sea” is null and void.

But this prayer means more than Jacob realizes, and the promise extends to more than just the next generation or the generation after that.

After all, one of those descendants is quite significant. One of Jacob’s sons is the Messiah. But Jacob couldn’t possibly know that. Or could he?

Jacob’s prayer — his heroic striving — is an appeal to heaven to let that Son be born, to let Christ come into this world of. But does Jacob know this?

I think he does. The promise of Christ was made long before Jacob. Back in Genesis 3:15 God said, “I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your seed and her seed; he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel.”

What could that have meant then? They were among the last words spoken before Adam and Eve were expelled from paradise, but those words — called by theologians the protoevangelium, the proto-gospel — were the “first good news” to be had after the disaster of the original sin took place.

That original good news was largely forgotten by the children of Adam, but one race in particular, Jacob’s sons and daughters, the children of Israel, are chosen by God not to forget it.

That is the point of Jacob’s struggle with the angel, and ultimately, of the widow’s persistence: to show that they have not forgotten it, that they have not given up hope.

This is why Jacob’s prayer is more significant than he knows. In response to Jacob’s demand, the angel changes Jacob’s name. Jacob, which means usurper, becomes Israel, he who strives with God.

III.

Israel’s sole purpose — both the purpose of the nation and the man — was to bring the Messiah to the world. You will notice I used the past tense there. That was Israel’s purpose. That purpose has been fulfilled.

Jacob was one of very few in his day who came to understand this. Many, even today, still do not understand Israel’s purpose. Certainly our Jewish friends have missed this point. They are still waiting for the Messiah to come.

The other so-called “Abrahamic” faith, Islam, has distorted Jesus beyond all recognition. But Jacob, almost alone among the men of his time, understood Israel’s purpose, that is to say, his own purpose, which is to see God face to face. For this reason, Jacob’s name is changed to Israel. His striving with God represents the hope that cannot let go, that cannot lose heart, because it is fixed on Jesus Christ.

The amazing thing about this story is that it is very likely that Jacob was wrestling with his own Son, that the angel was the Messiah, a pre-incarnate Jesus Christ.

How else can we explain verse 30, “So Jacob called the name of the place Peni′el, [the face of God] saying, ‘For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life is preserved.’”

Jacob was inspired by divine revelation to name the place Peniel. There is no other way he could have known that he wrestled with Christ, the promised Messiah. What he perceived by revelation we know as recorded history. St. John records that history for us in John 1:18, “No one has ever seen God; the only Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, he has made him known.”

Jacob hoped to see God’s promise fulfilled in his descendants, his messianic Son in particular, but few in his day shared that hope. For that matter, few share that hope even today. For while many know Christ and long for His return, many more do not, and hold His Word in contempt. Like the unjust judge, they do not fear God.

This is why Jesus tells the parable of the persistent widow. In this story, a widow demands justice from a judge “who neither feared God nor regarded man.” This makes him just like most, if not all our own judges today. It makes him a humanist, and, despite the name, men who have no fear of God lose all regard for their fellow man.

Humanism in its current form dates from the Enlightenment of the 18th Century. The humanist takes man as the measure, man as the standard, for all things and soon discovers that he has lost the idea of a standard altogether. At the very least, he has lost the notion of a standard that can be communicated one to another — one that can be the basis for the common good.

St. Paul describes such humanism in 2 Timothy 4:3, “For the time is coming when people will not endure sound teaching, but having itching ears they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own likings.”

The only thing Paul left out is that the time is not only coming, but has come, and is already here. Humanism was the philosophy of the serpent in the garden. Humanism was the idolatry of the kings of Israel and Judah. It was the justice of the God-unfearing judge. It is the standardless standard of our own day.

IV.

It is this humanistic system that Jesus confronts in today’s parable. Under humanism, skepticism reigns. Define a standard, attempt to call it an absolute truth, and you will find it deconstructed under the critical-progressive gaze.

There may be no standards, but that does not result in the humility needed for forbearance, or even for a libertarian to “go along to get along.” It is a fantasy to think that freedom without standards means that people will leave each other alone. In fact, it leads to coercion and the exercise of raw power, the kind that killed Christ.

The raw exercise of power is one way to describe the widow’s nagging. Hers is an example of coercion, a bribe. Luke tells us that the widow kept coming to the judge and that soon he’s had enough.

He says, “because this widow bothers me, I will vindicate her, or she will wear me out by her continual coming.” She steals his peace in order to bribe him with a promise to restore it, but only if he gives her what she wants.

There is no appeal to justice or to an absolute standard. This is a transaction, a quid pro quo. The judge himself acknowledges that he is ruling in the widow’s favor, not on the merits of her case, but so that she will leave him alone.

He says, “though I neither fear God nor regard man, yet because this widow bothers me, I will vindicate her.” He appeals to no other standard than what suits him, and what suits him is to be left alone.

What suits many Christians is to be left alone as well. That is why churches invite men and women into the pulpit who will scratch their ears and teach them doctrines that conform to the world, to standards other than the Word of God. Thank God, then, for Jacob’s chosen Son, who cries out to God day and night for our vindication.

In a crude way, the widow’s bribe foreshadows Christ’s blood payment for sin on the cross. The judge vindicates the widow and he regains his peace. Christ’s sacrifice satisfies the law’s demand, turning away God’s wrath, and restores peace between God and men.

There is a crude similarity just as there is sometimes a crude similarity between God’s wrath and humanistic justice. Both are total, but one accepts the sacrifice of one for the good of many, while the other sacrifices the good of whole for the perversions of a few.

V.

The one thing neither the judge nor the woman doubt is their own human agency: she with her persistence, he with his power to vindicate. Both see humanistic law as messianic. Both miss the Messiah Himself.

The widow expects the law to vindicate her cause and the judge never doubts for a moment that he is the agent of the law, a little messiah, a little christ, who is able to restore all things to this widow. But this is the very thing a religion of works cannot do, which is exactly what humanism is.

After all, there is no merit in the widow’s persistence and the judge possesses no power to restore life and health. Jesus can do both and that is exactly what the gospels show Him doing. In fact, the one time Jesus is asked to decide a civil case, in Luke 12:13-14, he declines. A person in the crowd comes to Him and says, “Teacher, bid my brother divide the inheritance with me.” To which Jesus replies, “Man, who made me a judge or divider over you?”

Jesus told parables to attack the humanistic religion and politics of His day. This parable is no different. The lesson for us is not to “pray more” to get what we want from God. Jesus concludes the parable saying, “Hear what the unrighteous judge says.” Very well, then. Let us hear him. This unrighteous judge says four things.

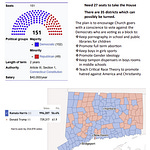

First, he says, “I neither fear God nor regard man.” The United States has two mottos, one official the other customary. The older, e pluribus unum, “out of many, one,” is the unofficial motto. It reflects the enlightenment sensibilities present at our founding, as if law, or a new constitution, or even a revolution had the power to unite, to make something whole.

The more recent motto, and the official motto, “In God We Trust,” dates from 1956, when this country’s biblical foundations were being dismantled by the Supreme Court. It was meant as a sop to conservative Christians and also made for good cold-war propaganda. Nothing makes me think Congress actually meant it when they adopted it.

Here we learn something important about humanists. They are often willing to do the right thing, especially when the elect put pressure on them. The idolatrous kings of Israel were happy to worship Jehovah, just don’t expect them to give up on Baal.

Second, the unjust judge says, “yet because this widow bothers me.” Religion works. I’m making a pun. Let me say it again. Religion works and humanism works because it is a religion of works. In fact any works-based religion — and that’s all of them, including the unbiblical forms of Christianity — is humanistic.

The widow knows what works. Bothering this judge will work and so she persists. Humanism works because it harnesses the power of man-made systems and licenses its use to men like the judge and women like the widow.

We’ve seen in our lessons for the last two Sundays that the Christian knows of a different source of power: faith, and through faith, the application of God’s law. Habakkuk 2:4 says, “the righteous shall live by his faith.”

Third, the judge says, “I will vindicate her.” Yes, but by what standard? Nothing about the parable should make us think he will vindicate her by God’s standard. We know nothing of the widow’s adversary. Perhaps the adversary was sent by God to judge the widow, in which case the widow is now demanding a judgment against God. All human justice is a judgment against God.

Paul warns against humanistic justice in Romans 9:20, “But who are you, a man, to answer back to God? Will what is molded say to its molder, ‘Why have you made me thus?’”

Again and again the parables of Jesus stress God’s absolute right to do what He will with His own. Two weeks ago we heard Jesus say, “When you have done all that is commanded you, say, ‘We are unworthy servants; we have only done what was our duty.’”

Fourth, and finally, the judge says, “she will wear me out by her continual coming.” Humanism eventually exhausts itself. What empire still stands? What world religion still inspires the heart? Our American empire still stands, for now, and barely at that. Islam long ago exhausted itself. Its present revival has more to do with revolution than revelation.

The men and women who rely on humanistic law to seek their ends soon find that their ends are frustrated, their spirits exhausted, and their souls damned to hell.

Did we not hear Father Abraham say three weeks ago to the rich humanist, “Son, remember that you in your lifetime received your good things, and Laz′arus in like manner evil things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in anguish” (Luke 16:25)?

So, when Jesus says, “Hear what the unrighteous judge says,” what does He mean? Jesus also gives an answer in four parts.

First, He asks, “will not God vindicate his elect”? It is God, not man who vindicates. It is the elect, not the reprobate who are vindicated. Any attempt at self-justification will be crushed.

When so-called same-sex marriage was legalized a decade ago, I said that those who justified themselves by the law in this way accomplished only one thing: they made themselves new creations — not by grace, but by law.

Like the widow, their persistence paid off. They were vindicated, yes, but vindicated by judges who neither feared God nor regarded man. Therefore, they received their so-called “justice” at the hands of those who hated them.

Second, Jesus says the elect are those “who cry to him day and night.” There is no merit in the widow’s wailing, but there is merit in the cries of the elect, particularly in the cry of the Elect One, Jacob’s greater Son, Jesus, who cried out to God from the cross for His vindication.

Three days later God the Father raised Him from the dead. What could be a more total and complete vindication than the resurrection of the righteous?

Whereas the humanist tries by legalistic means to transform evil into good and sin into righteousness, only Christ can effect such a transformation. Such alchemy is possible only on the cross.

Third, Jesus asks, “Will he delay long over them?” He then answers, “I tell you, he will vindicate them speedily.” Three days is not much time to wait, and it was not even three days. From the ninth hour on Good Friday to early Easter morning is less than 72 hours. Surely, God did not delay long over His Elect One, His Chosen One.

For us, who still wait for our vindication, we have to remember that we are not vindicated on the merits of our case. The case against us is open and shut. We are guilty and we deserve the death penalty. We can be certain the penalty will be applied, unless we happen to be alive when Christ returns.

It is of the utmost importance that we see Christ’s vindication as our own. That is the symbolism of baptism. If Christ went down into the water, we must go down into the water. If Christ came up from the water, we must come up from the water. If Christ went down into the grave, we must go down into the grave. If Christ rose from the grave, we must rise from the grave. Otherwise, as St. Paul says, our faith is in vain (1 Corinthians 15:14-19).

It is not that God has delayed our vindication. It is happening even as we speak. In just a few moments, in fact, we will baptize a young girl. That is the outward and visible sign — for all the world to see — of her vindication.

Fourth, and last, Jesus asks, “Nevertheless, when the Son of man comes, will he find faith on earth?” The question Jesus asks is not a sentimental one. He does not wonder if He will find any devotees throwing flowers at His feet or singing praise songs to Him when He returns. He’s asking if He will find His elect people doing their duty: “So you also, when you have done all that is commanded you, say, ‘We are unworthy servants; we have only done what was our duty.’”

This is why the reading from 2 Timothy 4:3-4 also sounds an apocalyptic note, “For the time is coming when people will not endure sound teaching, but having itching ears they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own likings, and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander into myths.”

Christians have to be careful that they are not listening to the modern echoes of these old myths just to get the results they want. We must stop our ears to them. The loudest ones we hear today always echo the humanistic tragedy of the garden, where, like the judge, our first parents proved they neither feared God nor regarded man.

But we need not lose heart. Our vindication comes from the One who not only obeyed God, but regarded man enough to become one. When our prayerful strivings cease, it will not be that we survived the ordeal of seeing Him face-to-face, but that seeing Him, we finally begin to live.

Preached on October 19, 2025, at the First Congregational Church, Woodbury, Connecticut (https://www.firstchurchwoodbury.org).