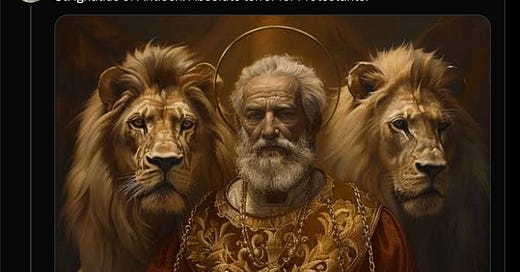

The first-century bishop, Ignatius of Antioch, is making the rounds in the past few days. Is he the scourge of Protestants and the doctrine of Sola Scriptura some say he is? Let’s have a look at the claims.

Apostolic Succession

All Ignatius ever refers to are the bishops appointed by the apostles. That’s it. That’s the succession.

No more apostles, no more bishops appointed by apostles. Some other source of authority is therefore needed. Hence, the need to canonize the Scriptures.

The criteria? Are the writings apostolic? Yes? Put them in the canon of the New Testament. No? Leave them out.1

After that, after the canon is fixed, the Bible emerges as the sole remaining apostolic authority for the Church.

Test of Canonicity

The test of canonicity was a writing’s apostolicity. That’s one reason Ignatius is not in the New Testament.

Ignatius emphasizes repeatedly, to every church he writes to, to stay in communion with that church’s bishop. Why? Because those bishops (and only those bishops) were appointed by apostles.

For Ignatius, the test of a bishop’s catholicity was the same as a writing’s test of catholicity. Was the bishop appointed by an apostle? Was the writing written by an apostle?

Roman Primacy?

Ignatius’s letter to the Romans shows a certain deference to both the imperial city and the church therein, but it is his only epistle not to enjoin the recipients of the letter to obey their bishop. Other than when referring to himself, the word bishop does not appear in the epistle.

Ign. Rom. 1:Intro, καὶ προκάθηται ἐν τόπῳ χωρίου Ῥωμαίων (“which also presided in the place of the country of the Romans”) simply means the church there presides over the city of the Romans. However, I grant that there are imperial overtones here, and with those comes a right to a kind of universal teaching authority, a ministry possibly referred to in Ign. Rom. 3:1, ἄλλους ἐδιδάξατε, “you were the instructors of others.”

But to say Ignatius thought that the right to instruct the Church was exclusive to Rome and her bishop would undermine his own authority to write letters to churches not his own.

Ignatius saw himself as an instructor of others too, as any bishop would. We are still a few centuries away from Augustine’s statement, “Roma locuta; causa finita.” (Rome has spoken, the cause is finished.)

No Authority Independent of Apostolic Authority

Ignatius makes the same point I am making. The church in Rome should listen to Peter and Paul because they were apostles. “They were Apostles, I am a convict,” he writes in 4:1.

Even though Ignatius can claim a legitimate apostolic succession for himself, he takes pains to distance himself from an apostolic authority that somehow inheres in himself, that is, in his own person. Likewise, he makes it clear that the church in the city of the Romans has no authority independent of the apostolic witness.

The Church’s Living Authority Today

We can’t use the Ignatian corpus to prove an apostolic succession of bishops that extends beyond those initial apostolic appointments. Apostolic authority ended with the apostles, except where their written testimony is preserved.

If I want to hear Peter speak today, I can hear him speak with full living apostolic authority wherever Peter is read in the churches. If I want to hear Paul speak today, I can hear him speak with full living apostolic authority wherever Paul is read in the churches.

The Church certainly had both the divinely appointed agency and the means to determine the canon, and continues to have a living, albeit derivative, authority today.

The Catholic Faith is always and everywhere the same because the Church’s living authority is founded on the apostolic witness, as Ignatius went to great pains to explain.

A reader on X made this comment:

1) Not every book in the New Testament is written by an apostle.

2) The apostolicity of a bishop is affirmed according to Ignatius by their predecessor entrusting them. This enables the Episcopal view of succession.

To which I replied:

1) The authority of every New Testament book is apostolic, whether copied down by a scribe or not. That was the test for inclusion in the NT canon.

2) Those predecessors entrusted their successors with the apostolic testimony. The test of a bishop was his agreement with the apostles (Ign. Eph. 11).

In the first generation, when authority in the church was still largely personal, rather than institutional, that agreement could be assumed if the bishop had been appointed by a living apostle, as in the case of Ignatius himself.

Later, after both the apostles and those whom they directly appointed had died, a need arose for a more durable apostolic witness.